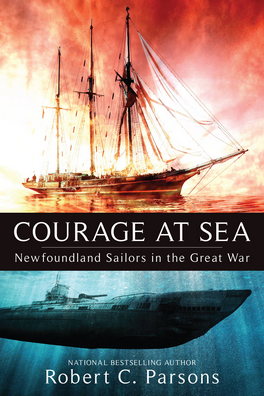

Courage at Sea

Newfoundland Sailors in the Great War

Courage at Sea: Newfoundland Sailors in the Great War is a collection of more than forty World War I stories involving the Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve and the Newfoundland merchant seamen who delivered goods to Europe in aid of the Allied war effort. Many foreign-going vessels carrying Newfoundlanders were apprehended en route by German U-boats and shelled, torpedoed, or boarded and bombed. Some of the crews were let go, but others were less fortunate. Some of the stories included are . . . Newfoundland’s First Decoration: Leander Green’s Story Men of Burgeo Rendezvous with the Enemy Torpedoed Three Times in Three Weeks The Story of Michael Foley, Harbour Grace Dictator’s Crew as Prisoners of War A War off Saint Pierre: SS Erik Great Honours to a Man from Pilley’s Island The Halifax Explosion: A Reservist Writes Home . . . plus many more. Robert C. Parsons is a winner of the Polaris Award and the author of more than twenty-five books on the nautical history of Newfoundland and Labrador. His book Courting Disaster: True Crime and Mischief on Land and Sea was a Globe and Mail bestseller.

“The First Newfoundland Seamen to Make the Supreme Sacrifice”

September 1914

In the fourth week of September 1914, Newfoundland learned of the first great sea disaster of the war. News came that British cruisers had been sunk by the enemy and there were many casualties. Newfoundland’s newly recruited Royal Naval Reservists had not yet been shipped overseas. Accordingly, no news was expected of death from those ranks. However, the next day local papers published The Roll of Honour, detailing the career of a Newfoundlander who had perished in the attack. It was Lieutenant Commander Bernard Harvey of St. John’s, an officer on HMS Cressy. Harvey, belonging to St. John’s, had been educated at Bishop Feild College and joined the England’s Royal Navy in 1912. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, the cruisers Cressy, Hogue, and Aboukir were in the North Sea in support of a force of destroyers based at Harwich, England. They were blocking the eastern end of the English Channel from German warships attempting to attack the supply route between England and France. In fact, these three ships were about to be decommissioned, retired from sea duty. That particular class of ship was becoming obsolete due to advances in naval architecture. However, at the outbreak of war they had a role to play and were staffed by reserve sailors from England. On September 22, the three cruisers were steaming in a line when they were spotted by the German submarine U-9. Although they were not zigzagging in a defensive manoeuvre, all of the ships had lookouts posted to search for periscopes, and one gun (afterward deemed to be woefully inadequate) on each side of each ship was manned. Unseen, U-9 submerged and closed the range on the unsuspecting British ships. At close range, the sub directed a single torpedo at Aboukir. The torpedo broke its back, and Aboukir sank within twenty minutes, with the loss of 527 men. The captains of Cressy and Hogue thought Aboukir had struck a floating mine and came forward to assist her. They stood by and began to pick up survivors. At this point, the sub fired two torpedoes into Hogue, mortally wounding that ship. As Hogue sank, the captain of Cressy, realizing that the squadron was being attacked by a submarine, tried to flee. The orders to leave the scene of a sinking was a new British war regulation, enacted to avoid another loss of ship and men. However, before Cressy got away, two torpedoes struck that cruiser, sinking it as well. A great number of men were rescued by HMS Lowestoft and by a little flotilla of patrol boats and armed trawlers. But among the missing was Bernard Harvey. In his overview, “Newfoundland’s Part in the Great War” in The Book of Newfoundland Volume One, Captain Leo C. Murphy says of Harvey: Bernard Mathieson Harvey, RN, who died on HMS Cressy, was the first Newfoundlander to make the supreme sacrifice in Great World War. The entire engagement with the sub had lasted less than two hours and cost the British three warships, sixty-two officers, and 1,397 sailors. Up to that time, the British Admiralty considered submarines as mere novelties, toys that would not amount to much in a war at sea. The battle silenced that opinion and established the submarine as a major weapon in the conduct of naval warfare. Britain, at this time, relied heavily on raw materials and certain manufactured goods imported from Canada and Newfoundland, including pig iron from the Sydney iron smelting plants. In the English factories the iron was reworked into finished products, both for domestic use and for armaments. Enemy subs and mines now added a new threat to importation from overseas. One of the ships that delivered iron from Sydney, Nova Scotia, to England’s ports was the 3,000-ton SS Sharon, commanded by Captain Cochrane of Nova Scotia. Sharon, built in Britain and owned in Canada, left North Sydney November 14, 1914, on a journey to Newport, Wales. Of the crew of twenty-five, the officers and chief engineers were British, but nineteen sailors were from the Maritimes, including four or five Newfoundlanders. After departure and somewhere off Newfoundland, a routine wireless message came to Sydney from Sharon, but after that, silence. No debris, message, or sign of the steamer was ever found, thus the final days and hours of Sharon passed from human knowledge. After a month it was declared lost with crew and believed to have struck a mine off Northern Ireland. Three Newfoundland sailors were: George Nelson Perham, born in Fortune and a resident of Nova Scotia, married with two children; Perham’s brother-in-law, Abraham Janes, a crewman; and Thomas Robert Stacey of La Poile, a deckhand. The name of a fourth sailor is engraved on a marble monument, a visible reminder of the loss of SS Sharon. His name can be found written on a memorial marker in a graveyard in the now-abandoned community of Port Elizabeth, Placentia Bay. It reads: “To a Dear Son, Archibald Senior, who was drowned on the SS Sharon, 1914, aged 35 years.” Newspaper items claim Sharon struck a mine while others say it was torpedoed. Some notices say it carried iron, others coal. Nonetheless, its story, brief and tragic, became a personal journey of the research and writing process for this author. Around 1998, it became one of the first tales I wrote of a ship and its Newfoundland sailors lost through the actions of war. That account of Archibald Senior’s memorial stone and the initial research of SS Sharon can be found in the Postscript on pages 201-204.These stories give an interesting and detailed account of the province’s many roles at sea during the First World War including the many Newfoundlanders apprehended during travel with a variety of outcomes. This is a unique look at the stories that were once lost at sea and need to be told as an integral part of our island’s history.-- Tint of Ink --

Shopping Cart

You have no items in your shopping cart

| Tax | Price | Qty | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No items in the Cart. | ||||

| Sub Total | $0.00 |

|---|---|

| Shipping | $0.00 |

| HST (15%) | $0.00 |

| GST (5%) | $0.00 |

| Total | $0.00 |